Disney’s upcoming live-action remake of Mulan has become a recurring topic of debate on social media recently. The movie is much-anticipated in China, but there are also critical voices suggesting the American Disney company “doesn’t understand China at all.” How ‘Chinese’ is Disney’s Mulan really?

Ever since news came out that Disney would turn Mulan into a live-action movie the topic has been frequently popping up in the top trending lists on Chinese social media.

The movie has been especially top trending on Weibo this week since the official trailer was released.

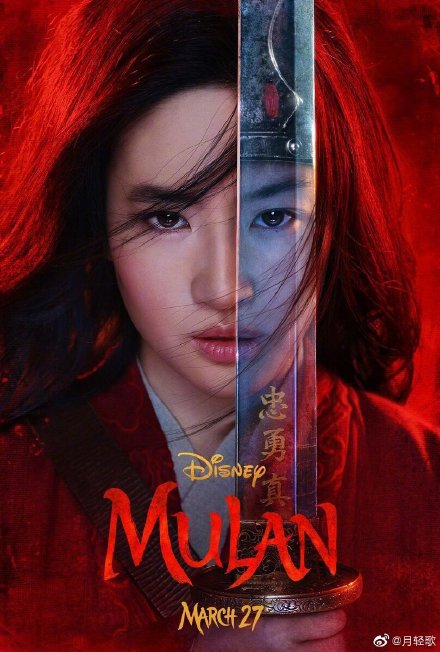

Mulan is the much-anticipated live-action remake of Disney’s 1998 animated Mulan movie, which tells the story of the legendary female warrior Hua Mulan (花木兰) who disguises as a man to take her father’s place in the army.

Over recent years, Disney has released and announced the live-action adaptations of many of its animated classics. Remakes such as Cinderella (2015), The Jungle Book (2016), Beauty and the Beast (2017), Dumbo (2019), and Aladdin (2019), have all been successful and, besides Mulan, they are now being followed up by the remakes of The Lion King, The Little Mermaid, Lady and the Tramp, and The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

Disney’s new Mulan movie is directed by the New Zealand film director Niki Caro.

The role of Mulan will be played by the (mainland-born) Chinese American actress Crystal Liu Fei (刘亦菲). The film also features Yoson An as Mulan’s love interest, Tzi Ma as Mulan’s father, Donnie Yen as Mulan’s Commander mentor, Gong Li as the evil witch, Jason Scott Lee as the enemy warrior leader, and Jet Li as the Emperor of China.

MULAN: WEIBO MANIA AND CRITICISM

“Americans really have no idea about China.“

![]()

Since the story of Mulan is a Chinese legend that has a history of over 1500 years in China, Chinese audiences are particularly invested in the topic of the upcoming Disney movie. Every new detail concerning Mulan seems to become another trending topic on social media.

On Weibo, “Disney’s Mulan” (#迪士尼花木兰#) has seen over 420 million views by now, while the hashtag “Mulan Trailer” (#花木兰预告#) alone received a staggering 1.2 billion views.

Following the release of the movie poster made by Chinese visual artist Chen Man, the relating hashtag (#花木兰海报是陈漫拍的#) was viewed more than 260 million times.

![]()

A topic dedicated to the missing Mushu, a talking dragon that is the closest companion to Mulan in the animated film, also received 310 million views (#花木兰里没有木须龙#).

Online discussions on Mulan show that there already is quite a lot of criticism on the movie and its historical accuracy, even though its release is still months away.

Some commenters criticized Mulan’s makeup in one of the movie scenes as being too exaggerated and unflattering.

The fact that the actors in the movie all speak English also did not sit well with some people, writing: “Why is it all in English?!” and “I understand the logic, but why would a group of Chinese people speak English while it’s filmed in China? Even if it’s a Disney movie, it seems awkward.”

Another controversy that has been especially making its rounds for the past few days is the one relating to the traditional tulou round communal residences that are featured in the movie trailer (#花木兰 福建土楼#, 170 million clicks).

![]()

The tulou are Chinese rural, earthen dwellings. Although the buildings are part of Chinese traditional architecture, they are also unique to mountainous areas in Fujian province. Not only is Mulan not from Fujian, her story also takes place long before these tulou were built – something that many Chinese netizens find “nonsensical” and “distracting.”

“Americans really have no idea about China,” some people on Weibo commented, with others writing: “We can’t expect Disney to research everything, but they can’t not do research. They shouldn’t let Mulan live in a tulou just because it looks pretty, she is not from Fujian!”

“Why on earth would she live in a tulou,” others write: “Isn’t she a northerner?”

“Foreigners just don’t understand China,” one among thousands of commenters said.

Another Weibo user writes: “Americans should first thoroughly understand the Northern and Southern Dynasties, and Chinese geography, and Mulan’s ethnic background, and then they can give it another try.”

FROM SELF-SACRIFICE TO SELF-DISCOVERY

“The meaning of the story of Mulan varies depending on how it is told, when it is told, and by whom it is told.“

![]()

Although many people outside of China only know about Mulan through the 1998 Disney animation that made the story of this Chinese warrior go global, Hua Mulan’s story has seen continued popularity in China for more than a thousand years.

The first known written version of the Mulan legend is the anonymous sixth-century Poem of Mulan (木兰辞), followed by other plays and novels in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (Edwards 2016, 19-20; Li 2018, 368).

Especially since the twentieth century, the story of Mulan has become a recurring theme in China’s popular culture, appearing in various plays, movies, TV series, operas, and even in games. Some of China’s earliest films were about Mulan; from 1927 to 1939, three different films came out on the female heroine, all titled Mulan Joins the Army (木兰从军).

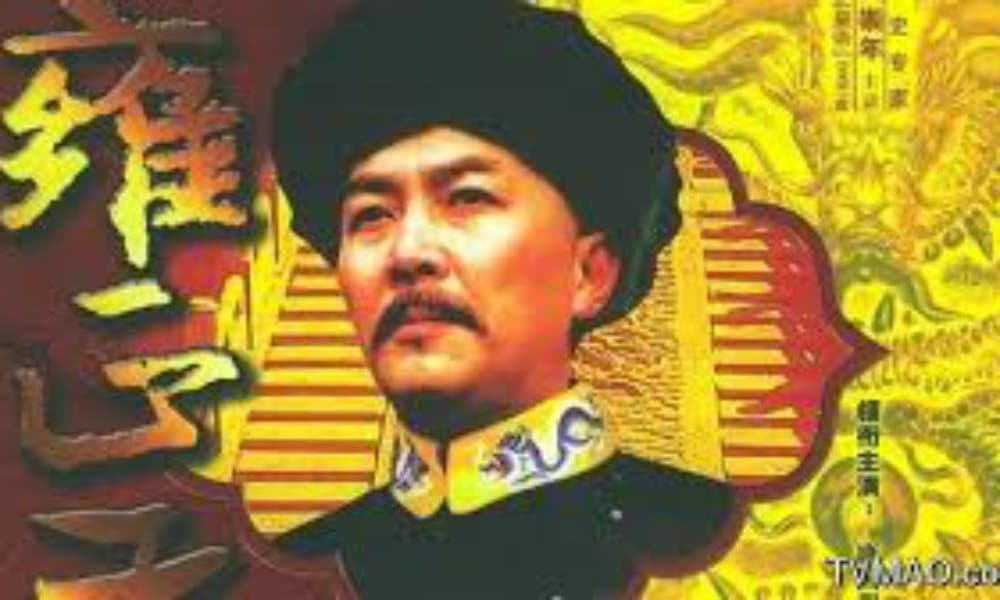

![]()

“Mulan Joins the Army” is a 1939 Chinese historical war about the legend of Hua Mulan.

The meaning of the Mulan legend varies depending on how it is told, when it is told, and by whom it is told. The story has seen a centuries-long period of change and development, with different perspectives being presented depending on the region and genre (Kwa & Idema 2010, xii).

The basic outline of the story is always the same: Mulan is the daughter who disguises as a man to protect her father and take his place in the army, where she fights for twelve years before being promoted to a high-ranking position by the emperor. Mulan declines and asks for an honorable discharge instead, so she can return home to her family. Once she is home, Mulan changes into women’s clothing again.

Chastity, filial piety, feminism, perseverance, sacrifice, militarism, patriotism – the Mulan story has it all, but which motives are given prominence is always different. Within China, the Mulan narrative is related to issues of China’s national identity and political goals.

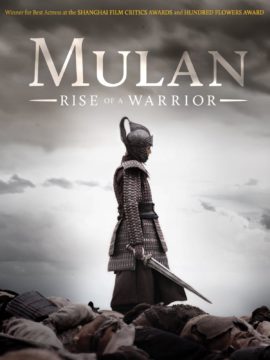

![]()

“Mulan: Rise of a Warrior” is a live-action film produced in mainland China in 2009.

In Chinese literary versions before the twentieth century, Mulan is presented as a northerner of uncertain ethnicity, a figure of resistance, who sacrifices her own safety to protect her father and show filial piety. Confucian values and the importance of family are at the core of the Mulan story (Edwards 2016, 19-20).

In Chinese versions after the twentieth century, Mulan is implicitly presented as being Han Chinese and as a “loyal patriot defending China.” The focus is no longer solely on Mulan giving up her own freedom for the sake of her father; it is her militarised sacrifice to the state and the importance of patriotism that is highlighted instead (ibid., 19-20).

With Disney’s 1998 adaptation of Mulan as an animated film, the main focus of the story was again shifted. Disney presented Mulan not so much as a patriot or as a Confucian daughter, but as a somewhat goofy and free-spirited young woman on her “Americanized self-realization journey” (Li 2018, 362-363).

Mulan’s individual coming of age and feminist story is echoed in the film’s Reflection song, in which Mulan sings:

“I am now

In a world where I have to hide my heart

And what I believe in

But somehow

I will show the world

What’s inside my heart

And be loved for who I am”

Although the narrative of the young woman who finds her own true voice resonated with many around the world – Mulan became an international box office smash hit -, it did not resonate with Chinese audiences.

In China, the Disney film grossed only about one-sixth of its expected box office income and was even among the lowest scoring big imported US films since 1994 (Li 2018, 362-363).

According to scholar Lan Dong, the Mulan flop in China indicated Disney’s failure to anticipate how the film would be received in China and how the Chinese audience’s familiarity with Mulan’s story had already shaped their expectations of the film (ibid.): Disney’s Mulan clearly was not the same as China’s Mulan.

THE DISNEYFICATION OF A CHINESE FOLK HEROINE

“The animated Mulan film clearly Disneyfied the story by playing into various American stereotypes of feudal China.“

![]()

But who is “China’s Mulan”? And who is “Disney’s Mulan”?

As described, Chinese versions of Mulan have significantly changed through times. And Disney’s Mulan of 2020 is also very different from the Disney princess that stole the hearts of viewers around the world in 1998.

Judging from the trailer, the upcoming Mulan will be a much more serious movie that focuses on the action and martial arts, and seems to represent Mulan as a self-sacrificing woman warrior (nothing goofy).

![]()

There’s an apparent risk in this route taken by Disney. On Chinese social media, the complaints about the movie relate mostly to the movie not being ‘Chinese’ enough when it comes to historical accuracy and language.

In English-language media, the movie is criticized for omitting the talking dragon and the songs and for “bowing to China’s nationalistic agenda” with its patriotic theme (Jingan Young in The Guardian, also see Vice).

The Disney company aims to entertain children and adults all around the world. In doing so, they convert “cultural capital” to “economic capital” and create content with universal appeal for global audiences, virtually always requiring commercial concessions to adapt to tastes and expectations of their mass audience.

![]()

Mulan merchandise, image via mouseinfo.com.

Since tastes and audience expectations change over time, it seems logical for Disney to make different choices for its Mulan feature film in 2020 than it did in 1998, and not only because the company might have learned from its past mistakes in mainland China. China’s role in the world, and how people view China, has also greatly changed over the past twenty years.

National cultures, stories, and legends go through a process of ‘Disneyfication’ once they became part of the Disney canon. The term ‘Disneyfication’ has been coined since the 1990s to describe this phenomenon and has been used in various ways since.

Speaking of globalization and literature, author David Damrosch (What is World Literature?, 2003) uses ‘Disneyfication’ to describe how many foreign literary works will only be translated and sold in the West when its content ‘fits’ the image audiences have of that certain culture. What remains is actually a ‘fake’ cultural product that holds up certain stereotypes and clichés in order to please the audience (Koetse 2010).

In the 1998 animated film, Mulan was clearly ‘Disneyfied’ by playing into various American values and stereotypes of feudal China that were most dominant at the time.

![]()

Although the upcoming Mulan movie will be very different from its animated predecessor, we already know that it will play with some of those stereotypes again in a way that you could call ‘market realistic’: viewers will see an English-speaking Mulan that lives in a traditional Fujian tulou building. Some of the sceneries and settings will have absolutely nothing to do with the authentic story, but much more to do with how viewers around the world now imagine China.

![]()

The movie will undoubtedly present folk heroine Mulan and ancient China in a way that is aesthetically pleasing and accessible, making Mulan and her story easy to understand, digest, and love.

WHOSE MULAN IS IT ANYWAY?

“For many Chinese viewers, Mulan has become ‘too American’, while foreign media criticize the film for being ‘too Chinese.’“

![]()

The irony in the criticism that has emerged over Disney’s Mulan recently, is that in the eyes of many Chinese viewers, Mulan has become ‘too American’, while foreign media criticize the production for being ‘too Chinese.’

This is by no means the first time the Disney company is under attack for the way in which it adapts local legends or stories into international feature films.

With Pocahontas, Disney was accused of “whitewashing horrific past,” the Moana movie was said to show “insensitivity to Polynesian cultures,” some critics found Aladdin to be “rooted by racism and Orientalism,” and recently, Disney’s choice to cast a black actress for the remake of The Little Mermaid triggered controversy for removing “the essence of Ariel.”

There are two sides to the controversial ‘Disneyfication’ coin. On the one hand, one could argue that some of the cultural value of the original local myths, legends, and stories are lost once they are transformed and simplified to satisfy mass market demand.

On the other hand, the Disney corporation also truly makes these local stories go global and in doing so, further adds to their cultural significance and worldwide recognition.

Mulan is now a Chinese legend that has gone beyond its borders and is no longer ‘truly Chinese’ – whatever that might mean. She has become a part of people’s childhood memories and popular culture in many countries around the world.

![]()

Just as The Little Mermaid no longer solely belongs to the realm of feudal Nordic folklore, Quasimodo no longer just exists in French literary canon, and just as Aladdin has become so much more than part of the The Thousand and One Nights, Mulan has also come to represent more than a Chinese folk heroine. She has become a world-famous woman warrior whose story will keep evolving for the years to come.

About the upcoming Mulan movie and its criticism, one Weibo commenter writes: “I find it hard to understand why people are so fussy. They have a problem with Mulan’s make-up, or with the fact that there’s no singing and no Mushu, or with the scenery. This is a movie. It can only stay close to the original work, but it will never be the original work.”

Luckily for Disney, many Chinese viewers are still very keen to watch the Mulan premiere despite – or perhaps thanks to – the ongoing controversies. The casting of Liu Fei as Mulan has also been met with praise and excitement.

Popular Weibo law blogger Kevin (@Kevin在纽约) writes: “On the first day that the trailer for Disney’s live-action Mulan was released, it had 175.1 million global views, making it the number two Disney adaption. The number one is The Lion King which had 224.6 global views [on its first day]. Although the Americans made Mulan live in a tulou, and made her speak English with a Chinese accent, it all won’t prevent Hua Mulan from having great success in 2020.”

Other netizens also agree, and they do not seem to mind sharing ‘their’ Mulan with the rest of the world.

“Some people are being too obstinate,” one female Weibo user writes in response to all the criticism: “This is the American Disney company, and all princesses speak English first. Jasmine in Aladdin also did not speak Arabic. I gather that in the film there will definitely be some subjective ideas or errors based on Western conceptions of China. As Chinese, we might find them misrepresentative or laughable. But from the trailer, I can already see that [this film] matches our esthetics and imagination. Most importantly, this film expresses the strength and beauty of Chinese women, and of women in general – that’s what matters.”

Discussions on Disney’s Mulan will certainly continue in the time to come. The movie is scheduled to be released in theatres on March 27 of 2020.

Too Chinese? Too American? Too Disneyfied? Too patriotic? Disney’s Mulan might not please all viewers. Fortunately, there are and will be dozens of other Mulan versions providing viewers and readers with new and different perspectives on the centuries-old legend. But who is the ‘real’ Mulan in the end? We’ll probably never know.

By Manya Koetse

(Harris 2005, 50).

Dong, Lan. 2010. Mulan’s Legend and Legacy in China and the United States. Bibliovault OAI Repository, the University of Chicago Press.

Edwards, Louise. 2016. “The Archetypal Woman Warrior, Hua Mulan: Militarising Filial Piety.” In: Women Warriors and Wartime Spies of China, pp. 17-39.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Harris, David. 2005. Key Concepts in Leisure Studies. SAGE Key Concepts. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Koetse, Manya. 2010. “The Imagined Space of Chinatown: An Amsterdam Case Study.” Leiden University, https://www.manyakoetse.com/the-imagined-space-of-chinatown/ [July 12, 2019].

Kwa, Shiamin and Wilt I. Idema (eds). 2010. Mulan: Five Versions of a Classic Chinese Legend with Related Texts.” Indianapolis/Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company.

Li, Jing. 2018. “Retelling the Story of a Woman Warrior in Hua Mulan (花木兰, 2009): Constructed Chineseness and the Female Voice.” Marvels & Tales 32 (2): 362-387.

Young, Jingan. 2019. “The Mulan trailer is a dismal sign Disney is bowing to China’s nationalistic agenda.” The Guardian, July 8 https://www.theguardian.com/film/2019/jul/08/mulan-trailer-is-a-dismal-sign-disney-is-bowing-to-china-anti-democratic-agenda [July 12, 2019].

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. Please note that your comment below will need to be manually approved if you’re a first-time poster here.

©2019 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

The post China’s Woman Warrior Goes America Again: The Disneyfication of Mulan appeared first on What's on Weibo.